Looking through some "stuff" I found a copy of "The CCK Paper" that cover the presentation of the Silver Star to the crew. I included a few other things.

Many of the stories related below have photos in various section listed above. As an example, there are photos from the PDM flights in the MISC section.

25 Nov 2012 - It is interesting in the last couple of months I have heard from several of my old crew.

These are a series of short stories of my experience in Vietnam as C-130 pilot.

I will add stories to the top if I decide to tell them. Some I can't or won't relate.

While the C130s were controlled by PACAF or TAC the requirements were different than under MAC. How many of the pilots remember when you would fly a GCA to a 2500 foot strip as 100/quarter mile visibility. When the C130s move to MAC that day the requirements became nothing shorter than 3500 and the landing minimums went to 200/half mile.

Note, I was one of the last pilots to go through a very detailed C-130 upgrade program. This program involved a lot of aircraft systems study. That background, and spending time with various maintenance shops gave me a better than average knowledge of the aircraft. This was pointed out during my upgrade to instructor pilot where I had a better knowledge of aircraft systems than the Check pilot.

I arrived at Ching Chang Kang (CCK) Taiwan on 29 May 1969 and departed 29 May 1973. I was assigned to the 345th TAS during this period. My wife spent about 13 months in Taiwan. I reason I am adding this short section is in response to a short document I place on my site. There are some misspelled names, which I will correct as soon as I find my map of the country. Thanks George Elwood

In Jul 1967 I was employed in engine service on the EL out of Cleveland. I continued to spend some time at Berea tower on the PC. I left the EL and went into the US Air Force. In September 1967 I started into pilot training at Moody AFB. Completing pilot training, I went specialized training in the C-130 at a base near Nashville TN. Being qualified, I went off to SEA as a copilot. Actually, I was based in Taiwan but we spent most of our time in Vietnam. I spent a year as a copilot, a year as a pilot and two years as an instructor pilot. Considering this was a 15 month tour, I enjoyed it enough to extend three times for a total of four years.

Flying C-130s was relativity safe. My squadron didn't lose many aircraft until I got married and had my wife with me in Taiwan. A week after my wife arrived we lost two aircraft, including one piloted by somebody my wife just met. While in Vietnam, my roommate from pilot training was shot down and killed in South Vietnam while flying a special purpose aircraft.

I never got a bullet hole in an aircraft I flew until the last day of the war. I took a mortar round though the wing while on the ground. We managed to get the aircraft out later that day. The bad guys were close as you could hear the AK-47s. The crew received a Silver Star for this effort. This action was written up in the book "Official History of Tactical Airlift in Vietnam." A few days later I had the opportunity to fly to Hanoi as part of the "peace" process. My picture appears in a C-130 soft cover book in Hanoi with some North Vietnamese Generals.

Arriving back in Taiwan, I received a call the next morning from the Squadron Commander asking if I wanted to go on a special mission. I said yes and left the next day to Clark AFB PI. Since I had been to Hanoi three times, I briefed the C-141 crews on processes at the Gia Lam AB in Hanoi. I was the pilot on the C-130 which brought in the US and international support team (see below). My crew was the third US people to meet the release POWs. We walked them from the sign out area to the C-141s. In the PBS feature last night, I saw my navigator walking out one of the POWs. I have seen myself in some of these movies of the POW release. This was the high spot in the time in SEA.

After we arrive in Hanoi for this release, we setup the CCT communications to support the C-141 operation. We also had the U.S. officials who would actually sign for the POWs. The NVA had set up a large tent in front of the operations building. It actually sat over a filled in crater from a B-52 strike in December.

I remember seeing some small buses near a hanger when we arrived. I didn't think about this until the first C-141 arrived and a small US Flag was displayed out the window of the bus. Now we knew the POWs were on the field.

This first release was for the POWs who had been held the longest and those most injured. The only person I can remember taking to the C-141 was a B-52 tail gunner who had been shot down in December. I was support one side of his stretcher. Initial each POW had a single escort to the C-141. We then determined that we could provide two people for each person. Some of the POWs wanted to talk while other where quiet. We explained what was going on and what to expect. I remember on POW asking what type aircraft he was going in. One asked about our flight suits

After all the POWs had departed in the C-141s, we reload the CCT equipment. Because some of the team had to go downtown Hanoi, we got out our box lunches and started to eat. After we completed this, an NVA representative invited us to a lunch in the operations building. After some discussion with the mission commander, we went into the building. The NVA had a large spread of food laid out for us. As I remember, it was most sandwiches and drinks. I did bring back a beer bottle from this meal.

Crews involved in later POW releases were actually driven into Hanoi during the breaks.

Since we had three crews on the aircraft, my crew was done for the day. The second crew flew from Hanoi to Saigon. The third crew flew the leg from Saigon back to Clark. We were gone for around 24 hours.

What is interesting is that Ed Mechenbier, one of the longest held US POWs, who was released in this first process, was also employed by SAIC in Dayton. He actually worked just down the hall from where I sat. Another interesting fact is that the C-141 that took the first POWs from Hanoi was based at Wright-Patterson and is now located in the AF Museum.

Because the enemy controlled much the road, especially at night, movement of artillery shells and other critical materials were normally made by tactical airlift. The large loads into bigger fields were handled by the C-130s. Smaller loads by C-7 and C-123 aircraft.

One morning our mission was to re-supply Song Be, located about 60 miles north of Saigon. My crew was scheduled to fly the first mission into Song Be. The first mission normally takes the Combat Control Team (CCT) into the site. The CCT provides controls of all aircraft operations and movement of offloaded materials to the users.

Song Be had a major artillery battery. In past visits where we actually went to the ramp to offload, you could hear the shell moving through the air. Song Be was located next to Song Be "mountain." Actually this was a high hill in the south, one of the few. The field was located just north of the mountain. As I remember, the field was 3500 feet long covered with metal planks. It was constructed across the top of a hill, which meant you actually had to be climbing during the landing.

This first mission went without problem. We landed, offload the CCT and their equipment and departed for Saigon. After landing in Saigon we loaded five pallets of Class "A" explosives, either 105mm or 155mm shells. The weight was 25000 pounds. After loading we were told to stand down due to enemy action at Song Be. It seems that the second aircraft took enemy fire and was damages. The crew had to put plugs in the wings to keep the fuel from leaking out.

Our crew returned to the crew lounge to await our next tasks. After several hours, the detachment commander asked me to return to Song Be and remove the CCT. He said that we would have air support from fighters. We were given the frequency of the Forward Air Control (FAC). We elected to take the 25K of cargo to Song Be rather than offload it. Once in the Song Be area we contacted the FAC. As it turned out, he was our fighter support. He was flying an O-2 (twin engine Cessna) heavily armed (??) with smoke rockets. His comments was "this should be interesting."

The first attempted landing had to be aborted due to heavy enemy fire on the runway. The next attempt was successful. In order to stop on this short field with a heavy load required heavy braking and reversing of the propellers. We stopped and turned around at the end of the runway.

Because the goal was to spend minimum time on the ground, we were to use what is called "speed offloading." The pallets are released and the aircraft pulls ahead. This permits the pallets to roll off the aircraft in about 10 seconds. In order to get the pallets to move you had to increase the power of the engines. This increase in sound of the engines was picked up by the enemy. The gunners assumed that we were getting ready to takeoff. They then fired several mortar rounds across the center of the runway. I noted the location of the holes for the takeoff roll. The O-2 fired a few smoke rockets toward the location of the mortars to keep their heads down for our takeoff. We loaded the CCT and took off without a problem.

There was a C-123 pilot who did something similar receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor for his efforts. The difference was that the Vietcong could be seen on the field.

I had taken leave in the US in 1972 to get married. I then returned to Taiwan with my new wife. I got to spend three days getting my new wife established in our rented house in downtown Taichung. Luckily, I had a friend from OTS living nearby with his family. These friends were able to help my wife through this transition period. We arrived on Tuesday evening from the US and I left for Vietnam on Friday morning. This is great way to start a marriage.

By this time, the C-130 operations were flying out of Saigon. The enemy had made a large push to overrun the country during this time frame. In one action, the enemy had surrounded An Loc, a city about 60 NE of Saigon. Inside the city were both US and Vietnamese troops. Because the city was surrounded, airdrop was to only way to re-supply the allied forces.

At the time airdrops were normally completed in formations of multiple aircraft. The first attempt to make this re-supply was using the normal daylight formation airdrop. The C-130 is not fast and in the airdrop mode is even slower. Using the container delivery system (CDS) the air speed is fairly low as the nose must be high. Needless to say, that an aircraft was shot down. This aircraft and crew was from my squadron. Luckily the pilot was able to crash land the aircraft and everybody was able to get out. The crew was recovered by Army helicopters using procedures developed on the spot.

This initial attempt pointed out that the normal airdrop procedure would not work. After this mission, it was decided that they would try night airdrop missions with individual aircraft. The mission planners decided to have the aircraft approach An Loc down a road, make the airdrop and then turn and fly out another road. It made for easy navigation, but made it easy for the enemy to setup anti-aircraft weapons along the road. A C-130 from my squadron was shot down with a loss of the entire crew. My wife had met the pilot of this aircraft the previous week.

The following night, my crew was scheduled to make the night airdrop. We were brief to use the same route as all of the other aircraft. After the briefing, the crew discussed the route and decided to modify it slightly. We decided to offset from the road about 1/4 mile until we saw the drop zone, a soccer field, fly an "S" turn in, make the drop and continued a few second beyond where we were to turn and then departed the area. Because of the heavy air operations in the area, we had to hold away from the area for over an hour. It was getting down to where I would have to return to Saigon to refuel when we were cleared in for the drop. This is one those hours of boredom followed by second of over whelming excitement. We flew as planned, made the airdrop and made our escape. When we returned to Saigon, checked over the aircraft and could not find one bullet hole, which was unusual for that night's operation.

The official end of the war was closing in. After the Rolling Thunder B-52 strikes against North Vietnam in December 1972, the North decided to "quit." With the end of the war scheduled to end the following morning, we were scheduled to move some South Vietnamese troops from Da Lat in the highlands to Da Nang. We were now flying out of Na Kon Phanom (NKP) in Thailand.

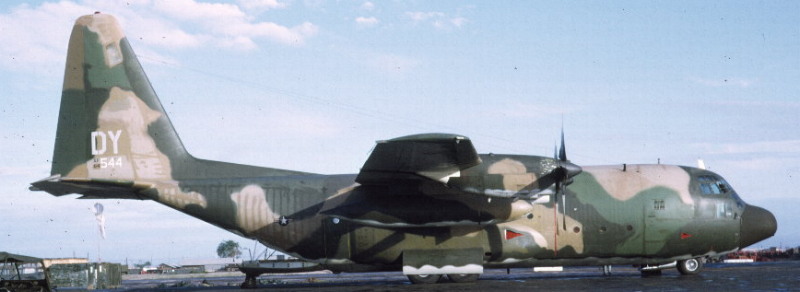

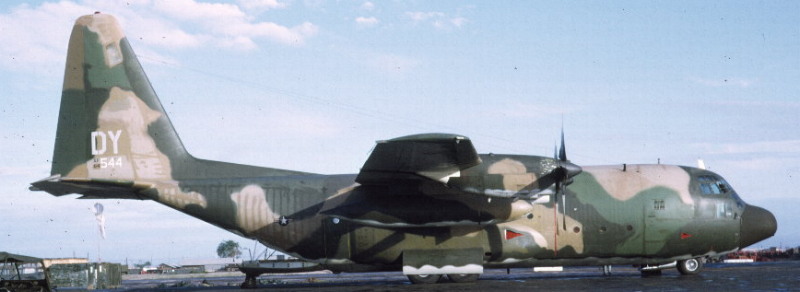

We landed without problems and taxied to the ramp area. Because we were hoping to complete several trips, we left the engines running. As we started loading the troops, we noted several explosions in front of us moving toward the aircraft. We shut down the engines and departed the aircraft as fast as possible. One of the mortar rounds when through the wing in the flap area on the right side of the aircraft and exploded on the ground along side the aircraft. The shrapnel from the mortar put holes throughout the aircraft, even up near the top of the tail. The tire near the explosion was holed and went flat.

Luckily, we were out of the aircraft and nobody was hurt. The enemy troops were fairly close in that we were able to hear the AK-47s. These weapons have a very unique sound. The U.S. and Vietnamese artillery fired toward the enemy troops. The US support forces showed up to provide some level of security, as I remember about three. Nothing like a bunker, which really couldn't stop a mortar round from the top. When a second C-130 arrived in the area, I attempted to warn the crew not to land using a survival radio. However, the aircraft landed anyway. As they taxied up, the mortar rounds started again. I disappeared in cloud of dust from a close by round. Again, luckily I escaped without a scratch.

After awhile, the enemy activity slowed down enough for the other C-130 to depart. We asked them to request a new tire, jack and support to help us change our flat tire. While the enemy activity was not directed at us, the firefight still continued around us. We could even watch some air strikes. It was important that we repair the tire and get out of Da Lat before dark. The US Army advisories told us that after dark the Viet Cong would destroy the aircraft. Later that afternoon, another C-130 arrived with a tire, jack and maintenance troops. Of note, a C-130 tire is NOT small or light. We had to develop a procedure to change the tire, as the normal process would not work. We did pickup a mortar round every so often, which drove us to the bunker. We finally got the tire changed and then discovered that the battery had died. Without a battery it is impossible to start the auxiliary power unit, which is necessary in order to start the main engines.

About that time, an O-2 arrived at the base. The pilot offered to let us use his battery. The O-2 battery was different than the C-130 battery. My flight engineer used pliers to connect the O-2 battery to our electrical system. He had to wear gloves, as the pliers got hot from the current being passed through them between the O-2 battery and the C-130 electrical system. While the engineer held the battery, I started the GTC and then one of the engines. Once this was completed, the engineer gave the battery back and we got ready to leave.

Because of all of the holes in the rear of the aircraft, we could not pressurize the aircraft, which was no problem. We also had some small holes in the wings, one of which may have been in fuel tank. Because the runway was not real long or wide, I elected to start all four engines and then shutdown the one closest to the probable leak after getting airborne. The C-130 is capable of taking off on three engines if necessary. We were able to get airborne without problem and shutdown one engine. We also noted a leak in the main hydraulic system, the one that operates the landing gear, flaps and half the flight controls. We had to shutdown this system. It was a quiet hour flight back to NKP.

The crew went over the emergency procedures and landing airspeeds. Because of the probable fuel leak, we would not be able to reverse the propellers after landing. Because of the hydraulic leak, we could not extend the flaps very much and the main braking system with the anti-skid capability would not be available. Without the flaps, the airspeed would be much higher. NKP had a longer runway, but it still wasn't that long, especially with the higher approach and landing speed. The emergency equipment was out in force for our landing. Luckily, everything went as planned. I did use the entire 8000 foot runway, stopping only using brakes carefully as the anti-skid was inoperative. This was the last full day of the war and after nearly four years and nearly 3000 flying hours, my first bullet holes.

After the above experience, the truce documents required that the US provide transportation for North Vietnamese from Hanoi to Saigon. The C-130s in-country were tasked to provide this support. The South Vietnamese define a specific flight path for operation of these flights in their part of the country. Most of the C-130 operation had been moved to NKP in Thailand.

For the first flight, the Wing Commander took my crew and his instructor pilot for the mission. The next day, I was the aircraft commander for the second flight. The weather was acceptable, but then tactical VFR (visual flight rules) were pretty lose. Our mission had us flying from NKP to Saigon and then to Gia Lam airfield in Hanoi, back to Saigon and NKP. It was interesting during the approach and landing, as you didn't know what to expect. You could see the SAM rings around the city. Gia Lam airfield is actually located across the Red River, north of Hanoi. During the approach for landing we could see the Dommer Bridge, with several section down. During the rollout we passed hidden radar units and Migs in revetments. The airfield had been a target during the December Round Thunder operation and showed damage. The NVA had filled in a large hole from a B-52 bomb in front of the operations building. Another bomb had hit the rear of the building. Of course there were no windows left in the building.

We loaded the NVA generals for the trip back to Saigon and departed as a two aircraft formation, turning to the north flying over what use to be a rail yard that actually looked like the moon with many craters. The two aircraft flew southeast down the Red River to the South China Sea. Since the weather was not all that good, I climbed to get on top of the clouds before the second aircraft did the same. We flew the published instrument approach to the field. This box descending box pattern had us fly over many star shaped SA-2 missile sites. It was on this flight that my crew had their picture taken with some of the NVA General we were carrying to Saigon. One of these photos is in a soft cover book on C-130 in Vietnam written by Sam McGowen.

On my second trip to Hanoi before the POW release, took these photos. It was a busy day as we went in two ship formations. When we departed two more C130s landed to move more to the NVA staff south to Saigon. I didn't remember but there appear to be an US Army LTC and enlist type with us. It also appears that we may have had some cargo for the US POWs. The slides were not numbered but I attempted to put them in order. As I remember, we were lead in a two aircraft flight on the north bound leg.

One night at Ubon Thailand while offloading class "A", we picked up an F-4 drag chute. The Air Force F-4s required a drag chute after landing to assist in slowing the aircraft down. We repacked the chute and hung it in the bomb shackle in the C-130. We chained the chute to the ramp. When we would go to a fighter base, we would request a tactical overhead approach like the fighter flew. On the downwind leg, the ramp door would be opened. After we touched down, the loadmaster pulled the emergency release handle and the chute would be dropped out the back. Because it was so small, it didn't affect the aircraft but we sure received interesting hand jesters from the fighter types.

One time doing this at Saigon, the Vietnamese traffic controller said, "Spare 619 . . . Spare 619 you have a good chute."

While most of my time was in Vietnam, we did have other mission. One mission involved supporting the Coast Guard and others on small island in the South Pacific. The mission involved flying from Taiwan to Guam. We would stage from Guam by flying missions to various islands.

For those of you into World War II history, like I am, these islands will sound familiar. On mission was to YAP. This was interesting as part of the filled used for the runway was Japanese Zero aircraft. You could see the tails sticking out of the dirt along side the runway. We got to go to Turk Island. Unfortunately, I didn't have time to check out the harbor area.

The next day we flew to Ponapa island. We had to stay overnight since we had to make an airdrop on Kisk Island the next morning. Since we got there early, we hired a cab and drove around part of the island. It was interesting to see fields of small Japanese tanks. The gun size appeared to be about 37mm. The next morning we took off to drop supplies at Kisk Island. While this island appears to be fairly large, it didn't have a runway. We had to at a specific time in order to drop the supplies in the water off one of the beaches. We also dropped mail on the beach.

Photos in MISC section.

While the conflict in SEA moved along, the US was looking in other areas. One of these sites was Diego Garcia. This is an island 17 miles long by 2000 feet wide. It is shaped like a horseshoe with the mouth about 1/2 mile wide. The mouth was wide enough for ships to enter into the lagoon.

When construction started on this British island, the runway was very short, C-130 size. It is now B-52 sized. Crews stationed in Thailand were tasked to fly supplies, mail, etc. to the people stationed there. The flight is very long and the alternate landing areas are in Southern India, some 400 miles north. The Air Force was contracted by the Navy to fly these support missions. The Air Force contract called for a specific amount of cargo for each trip and was based on the maximum gross weight of the C-130 minus the fuel required to fly there. The missions launched from Bangkok Thailand.

What I found interesting was being used to short field takeoffs, the takeoff from Bangkok used a lot of the available 10000 feet runway. As I remember, the takeoff weight was at the C-130 normal maximum of 155,000 plus or minus a couple of thousand pounds. Two thousand extra pounds of fuel was good for another hour of flying. After departure from Bangkok, we flew south to the southern tip of Thailand, and then SW to the middle of the Indian Ocean. Once you left Thailand, you didn't talk with anybody. The HF radio wasn't very good in the area and nobody really controlled the air space. We were able to contact the folks at Diego Garcia to left them know we were on the way. They had a really strong radio station, which we used to home on the island.

Remember, this was in wartime environment so rules, while in effect, were not enforced as they are today. This was also a time where air crews received really good training on aircraft systems and not the phase, "if the lights is on call maintenance."

The war was over. We didn't have a lot of presence in SVN. All C-130 operations were now based out of Thailand. We had a mission from U Tapao to someplace in SVN and then back to Thailand. First thing to go wrong was generator contact would operate correctly. This was before we left U Tapao. We called maintenance but the troop they sent didn't know much so we told him to leave and we took the aircraft. While you are not suppose to fly this way, it is permitted to fly IF you can monitor the generator to ensure it is still working, which we could. NOTE: If a main generator failed in flight and the indicator showed that it had failed, you had to shutdown the engine. The generator is directly connected to the engine gearbox and a failed generator could catch fire unless the engine was shutdown. New C-130s have a capability to disconnect the generator from the gearbox.

Flying east over Cambodia, we got a turbine overheat light. Nothing else point to a problem so it appear to be a faulty warning. We made a stop at Saigon to check the engine. We found nothing wrong, pulled the warning indicator circuit breaker and continued the mission.

On approach for landing at Udorn Thailand, one of the gyros went out. It was VFR so no problem. Landed without problem, offloaded and pressed on back to U Tapao.

Another mission, this one a couple of years earlier. Again, another mission in Thailand. This was a re-supply mission covering most of the bases in Thailand. We had different engines problems throughout the mission. We had decided on the second last leg of the mission, that we would shutdown the engine with the most problems. Of the four engines, only number three was operating correctly.

We were starting the engines at Taklhi for the last leg to Bangkok. The engine start process requires that number three engine is started first. During the start, a hydraulic line in the engine broke dumping most of the hydraulic fluid from the primary system on the ramp. With the option of staying overnight in Taklhi or pressing on to Bangkok, we decided to press. Starting the outboard engines we taxied out. The primary hydraulic system was refilled. Once we were cleared for takeoff, we started the other two engines on the runway and took off and immediately shutdown number three engines and pressed on to Bangkok.

As noted above, the C-130 went into shortfields. We were permitted into fields as short as 2500. New aircraft commanders are taught to make a steep approach to shortfields aiming at a point a 1000 feet before the landing area (200 - 500' from the end of the field). As you became more proficient, you moved the aim point closer to the end of the runway. As an instructor I was very proficient and my aim point was the end of the runway.

While demonstrating landings at a field south of Saigon, one of the Army helicopter pilots asked if we were doing auto-rotations. This is an emergency procedure that helicopters used if the engine fails. In the C-130 you get the aircraft configured with landing gear extended and full flaps, and pull the nose up to decrease the airspeed. Once the end of the runway disappears under the nose, you pull back the power and approach at maximum approach airspeed, which is close to stall speed. You have no energy left so you can't round out, but must increase the power of the engines to break the decent.

Because the VC were bring in shoulder launched surface to air missiles, the C-130 crews were required to remain as close to the airfield as necessary. I was flying with a Col one day and we were showing how well we could fly. Coming back to Cam Rhan Bay, I approached the field at 10000 feet on downwind. Normal downwind is 1500 feet above the ground. I configured the aircraft and pulled off the power when I passed the end of the runway. Falling off on wing I was able to get a good rate of decent. As long as you don't pull back on the yoke, the aircraft won't stall. I rolled out on final a 1/4 mile from the end of the runway and made a good landing.

Flying with the Col again, again approaching Cam Rham Bay from the north, I said that I could make the entire approach without touching the power. We were cleared for a straight in approach. I set the power and worked on energy management. I got the aircraft configured and landed without touching the throttle until I was on the runway. I flew the 15 miles without touching the throttle.

Our mission for the day was two trips from Saigon to Marine field north of Hue near the DMZ. The C-130 normally flew at 14-18,000 feet. At this altitude, the engines used about 1500 pounds per hour per engine. After the second mission, we decided to see how high we could get. Passing just west of Da Nang we reported in with the military radar site. We reported passing 26,000 feet. The controller asked us to repeat our call sign and confirm the aircraft type. We managed to get to 36,500 feet that night. The total fuel flow for all four engines was less than 1000 pounds per hour at that altitude. Individual fuel flow was about 250 per hour. 30 miles north of Saigon, I pulled the power to idle, fuel flow fell to about 50 pounds per hour. We used substantially less fuel during this return flight.

After this altitude got out, many other aircraft commanders worked to break this record. I don't know it anybody every got higher. I believe that the C-130 altitude record is held by a C-130A that was stripped. As I remember, the altitude was over 40,000 feet.

As one of the senior instructor pilots, I received the problem children. One of the tasks was to qualify new pilots for operation in theater. I received a new pilot to qualify for theater operation. This individual had just been upgraded from co-pilot to aircraft commander before departing from the US. As I found out later, I was the third IP to try and qualify this person.

The mission was in Thailand, which was easier as TAC operations were not necessary. It didn't take long to realize that this new pilot was not qualified and probably would never qualify. His control and knowledge were far below standards. One example that still sticks in my mind was a lack of knowledge in bold face procedures. In the aircraft operating manual, section three is the emergency procedures section. Certain emergency tasks must be committed to memory and must be second nature as they are critical to safety of flight. These include engine fires, go arounds, etc. The entire crew knew we had a problem. Coordinating with the entire crew, I planned on simulating an engine failure after takeoff. If was to start at the required minimum altitude. The takeoff proceeded normally. Arriving at the defined altitude, I pulled an outboard engine to idle and announced a simulated engine failure. Bold face procedures require a specific set of steps that must be completed in a specific order. This individual not only didn't start any of the bold face emergency procedure but didn't even apply flight control correction so the aircraft started to drop off. I took control of the aircraft.

I seldom wrote up a student. However, when I return back to CCK Taiwan, I typed up a three page report on the entire mission. A few weeks later, this individual was my co-pilot for an instrument check ride. He basically didn't help me at all. He was also receiving a check ride at the same time. After he got off the aircraft, the check pilot told me I would be seeing him again as he had failed his check ride. I told the check pilot to check my write-up in the squadron. This person became a briefing officer.

One night, we were scheduled to fly a blatter bird mission. This configuration was used to move fuel to out lying fields. The C-130 carried two large rubber blatters on pallets which held several thousand gallons of fuel, normally JP-4 (jet fuel). The mission was to deliver this fuel to a small north of Pleku in the Central Highlands of SVN. This was a typical short field operation. When we arrived at the field, we contacted the CCT on the ground. They said that they didn't need the fuel and further more, the offload area was targeted by the VC and loss of an aircraft was pretty high.

After this conversation, we contacted the Airlift Control Center (ALCC) at Saigon. This turned into a three way conversation trying to decide what to do. After an hour, it was finally decided we didn't have to land and off load the fuel. We recovered at Pleiku and refuel our aircraft from the fuel in the blatters.

We had a mission to move equipment from a short field in southern SVN. For people who are not familiar with anything type of aircraft landing, the pilots use many reference points. This field was cut out of a rubber plantation. The rubber trees are fairly high, with the field located in the middle. On my first attempt, my outside reference pickup the tops of the trees, which were some 50-75 feet high above the runway. This then caused my to start the landing process, much too high. I went around and tried again with the same results. I was able to refocus in the third attempt and made a successful landing.

Another night mission to the same field as noted above in the blatter bird story. The area was active with VC. We were to deliver four pallets of Class "A" shell. Because of the weather and location, we used a GCA (ground controlled approach) approach. This is the typical procedure and not a problem. Because of the enemy activity, use of outside lights was not acceptable.

The blacked out approach was made without a problem. In order to pickup the stripes at the end of the runway, the co-pilot would turn on the landing lights just before you came over the end of the runway. Lights on find the runway, land, lights off. Roll to the end of the runway, do a speed off load and get ready to depart. As I remember, the total time on the ground was less than 2 minutes.

I also remember that one of our crews actually hit some of these pallets during the takeoff process one night. Luckily the aircraft was not damaged too badly and they were able to get it back home.

A daylight mission to a 2500 foot airfield north of Hue near the DMZ. The weather that day was really bad, 1/4 mile visibility, 100 foot and rain. At the time, this was the minimum weather approved for C-130 crews. Again, this was a GCA approach. The process, make the approach, break out of the weather, pickup the runway and the end stripes, round out and land. The metal covering the runway, when wet is very slippery. This made stopping difficult.

We had a night mission to Hue. After landing, we off loaded, reloaded and were ready to start the engine. The starters on the C-130 use high pressure air. The starter is located on the rear of the gear case behind the propeller. While starting the number three engine, the starter shaft broke, which meant we couldn't start the engine. We called the ALCC in Saigon and notified them of the problem. Rather than sending out another starter, they indicated we use employ a blow start. This involved another C-130. The front aircraft would increase the power on his engines, increasing the air blast. The aircraft with the broken starter would be located immediately behind this aircraft. The air blast would then be used to turn the propeller of the second aircraft, which would then be started.

Before we could do this procedure, it was necessary to remove the broken starter. Normally maintenance troops would do the work, but there were no such troops at Hue. So the flight engineer and I removed the broken starter. Again, the normal process would be to use a maintenance stand. Being away from maintenance equipment, we ended up using a pallet on a forklift. I stood on one side and the engineer on the other. Working in the dark with flashlights, we were able to remove the starter and place a pad on the hole.

We had to wait until the daylight for the next C-130 to arrive. We started the engine and departed. Hue actually had a fairly long and wide runway and I could have made a three engine takeoff if there had been enemy activity.

After finishing a tour in Vietnam, normally 14-21 days, the crews would be rotated back to Ching Chang Kang (CCK) AB Taiwan. Because major repair capability didn't exist in country, the broken aircraft were returned to CCK along with aircraft needing additional maintenance not available in country. These daily flights resulted in a continued rotation of crews and equipment.

The one return trip I remember occurred after getting shot up, the three trips to Hanoi and before the first POW release trip. At the time we were flying out of Na kon phanom (NKP) in Thailand. We could support the war effort but were not in Vietnam and therefore we didn't count against the number of US troops in-country.

There were two aircraft to return to CCK on this day. The one we had was broken "slightly" and the other would be used for returning crew. As I remember, we did have some C-130 parts to return to CCK. Both aircraft were set to depart close together. As I remember, we were to depart second. NKP was located a few miles west of the Mekong River and Laos. While Laos was still an activity enemy area, we continued to over the country moving between Vietnam and Thailand. Because of enemy activity, many of the C-130 pilots would not fly over the country unless they were fairly high.

The passenger C-130 took off on an IFR (Instrument Flight Rules) flight back to CCK. The route of flight had the aircraft turn west into Thailand, climbing and then turning south to pickup an airway (Amber -1) which ran from Bangkok to Da Nang and then over water to the FIR control point "Sandy." Having flown many mission over Laos, I had no problem in fly over this country. We departed VFR (Visual Flight Rules) with a climbing turn to the east over Laos. Our route of flight took us directly overhead Da Nang.

As we approached Da Nang, we contacted Saigon Center and requested an IFR clearance from over head Da Nang to CCK. This was granted and off we went. We were approaching "Sandy" before the other aircraft was reporting into the Saigon FIR.

There were three basic mission types flown in Vietnam by C-130s. The first is the normal cargo mission. These were scheduled, more or less, and operated on fixed schedules to specific bases for routine cargo movements. The second type of missions were the add-on cargo re-supply sorties. These operated as required to wherever there was a requirement. The last type was a scheduled passenger mission. These missions were scheduled to support routine passenger movement within the country. The C-130 was configured to seat 78 people in rag seats. The seat were set up down the sides of the aircraft and also down the middle. Not something you wanted to sit in for very long.

The mission that I remember occurred during the rainy season. During this season, thunderstorms occurred over the country making operations interesting. We were operating out of Saigon at the time. The normal process was to select passenger to sit on the crew bunk in the cockpit rather than have to sit in the back. The selection process resulted in females being picked. The selection for the last leg of the mission into Saigon was a couple of "donut dollies", i.e., Red Cross workers being moved into the cockpit.

While flying between bases wasn't that bad as you could fly around the storms, landing was another story. There was a pretty good storm sitting over the approach end of the Tan Son Nhut runway, which we would have to fly through. Because of the storm, we would have to make an instrument approach and landing. We notified the passenger to make sure they were secure and started the approach. If you have every flown through a storm, you know it is really rough. This storm was no exception. It didn't take long for the passengers to start to throw up. Once one person did this, it spread throughout the rear of the aircraft. The two passengers on the flight deck also used the barf bag. The aircraft had to be washed out with a fire hose after landing.

I was flying a special operation mission north of Da Nang one night in late 1969. After the mission, we would have to recover at Da Nang to deliver products. Approaching Da Nang, the circuit breaker for the instrument lights popped. There is nothing like trying to flight an instrument approach, more or less, in the dark, both inside and outside. I was a copilot at the time in the right seat. After the pilots lights went out, he passed control to me as I still had some light. Then my instruments lights then went out. While the runway could be seen some 12 miles ahead, you still needed references in order not to hit one of the hills in the area. I was able get my small flashlight into my mouth in order to provide light on the instrument panel until the lights could be restored.

When I first started flying South Vietnam, the C-130 operation was out of Cam Rham Bay. This was fairly nice as we had acceptable quarters. The area was relativity safe as the Korean were providing security in the area. The Viet Cong did not like the Koreans and stayed away from the area so we seldom had any rocket attacks.

We were briefed that during a rocket attack we were to get on the floor toward the wall for protection. All around the buildings were five feet high concrete walls. These walls would stop fragments from rockets from hitting the building. These building were two stories high, which meant that aircrews upstairs would not be behind the walls.

As the war evolved, the Koreans were moved further north and our protection was provided by the US and South Vietnamese. Once the Koreans were gone, we could expect to receive at least one rocket attack per week. The crews got to the point that they would not move during and attack, not even to get on the floor. The closest a rocket hit to one of our buildings was less than 100 yards. This was one of those, heard the explosion, roll over and go back to sleep.

I was flying special purpose missions out of Cam Rham Bay as aircraft commander in 1970. Even though there was a war going on, you still have a maximum number of hours you could fly each month and three month period. Our crew had run up against this hours limit and were given a few days off. We could anyplace we wanted, as long as we didn't leave South Vietnam. So off we went to Cam Rham Bay Army airfield, across the bay to the west. We got on the first available Army helicopter going someplace. The first night we spent at the Air Force C-123 base located 20 miles south of Cam Rham Bay. The next day we flew to Saigon on a C-123. The next night we stayed with some Army troops at a fire base in the hills. The next night we spend with the Army at a base north of Cam Rham Bay. In our travels, we got to travel in many different types of aircraft, both Air Force and Army.

After we lost more aircraft while trying to re-supply An Loc using low level airdrops, a new process had to be develop. The C-130s were at the time dropping the heavies bombs. The fighters and bombers dropped bombs weighting either 500 or 750 pounds each. The C-130 started using bombs left from the B-36 days weighting in at 10000 pounds. The bombs were used to create helicopter landing sites in the jungle. The C-130 would be directed to the selected site using a specialized radar. This radar, as I remember, was developed to support the early ground launched cruise missiles in Europe (Matador). As these 10,000 bombs were used up, a new 15,000 pound bomb was developed.

The bomb was mounted on a pallet with two different parachutes. The first was a drogue chute which was connected to a much larger extraction chute. The drogue chute would be deployed on the run in to the target. The approach was basically an airborne GCA to a specific point in the sky. At the release point, the drogue chute would pull the main chute out and this would pull the bomb out of the aircraft. Once out of the aircraft, the bomb would separate from the pallet and move toward the ground. Normally a jungle penetration fuse was used to get the bomb to explode slight above the ground. I never flew any of these missions.

Because the low level missions were being dropped, we went to a GRADS type drop. The cargo was mounted in CDS containers. The cargo containers were placed on top of 20-24 inches of honeycomb cardboard. The chutes were designed to reef, i.e., remain mostly closed by means of small timed explosive cord. The timer was set to fire above the ground so that the chute would open with enough time to slow the decent. These timers were not all that good so the timers would either fire early which would cause the main parachute to open early and take the load into enemy areas. These loads would then have to be destroyed by fighter strikes. Some of the timers would not go off so the loads would hit the ground too fast.

During my checkout on this procedure, I had the opportunity to go to the cargo compartment and watch the drop. The Viet Cong had managed to move a 57mm anti-aircraft weapon to the area. They were firing at the C-130s making the airdrops at 10,000 feet. Luckily the gunner was a one level and all of the shots were well behind the aircraft. I could see where we had been by the small black clouds behind us.

All aircraft require a periodic major overhaul. These overhauls, Programmed Depot Maintenance (PDM), are completed at specific facilities in the U.S. The C-130 in a combat environment with max effort landings, stress the wing structures. The wings on the C-130 would therefore have to be replaced. Most of these replacements were done by Lockheed in Georgia. Therefore, the C-130s at CCK would be flown to the US for these repairs.

After being at CCK for 18 months, I had the opportunity to fly or ride back to the US on one of these missions. During this trip back to the US, I met my future wife on blind date.

A year later I had the opportunity to fly one of these PDM missions. One thing about the Pacific Ocean, it is REALLY big. The first leg had us flying from CCK Taiwan to Wake Island. This is a 10-12 hour flight with few reference points along the route. I believe the only reference point along our route was Iwo Jima.

After passing Iwo Jima, we lost the LORAN, our long range radio navigation system. Wake Island is a very small point in the middle of the Pacific. Add this to thunderstorms along the route, which required flying around the storms. This makes for interesting navigation, basically coming down to good guessing. Using the available capabilities, the navigator could developed a LOP (line of position) based on the sun. To get a point along that line, you need another reference point, even the moon would help.

We continued to climb as fuel burned off. This increased our range and improved the range of our available navigation instruments, VOR and TACAN. Luckily, Wake Island radar found us, some 150 south of track and we were able to land without a problem. We did get the LORAN fixed prior to departure for Hawaii. The rest of the flight to the PDM facility went without problem.

While home, I got engaged. I did come back to the U.S. about six months later to get married.

The return trip to CCK was another interesting trip. The crew was to pickup the aircraft at Fort Lauderdale FL. As per normal, the aircraft was not ready to depart when the crew arrived. We were able to rent a car and drive across FL to Cape Canaveral. There we got a special tour, which included seeing one of the rockets getting ready for a flight to the moon.

After a week, we finally got the aircraft ready to go. We departed late in the afternoon with a destination of Little Rock AR, a major C-130 base. During the climb out, we got a low level oil light on the number three engine. This required a shutdown. After a week in beautiful FL, we decided to press on to Little Rock on three engines. It was determined that the turbine seal had failed. The maintenance folks at Little Rock removed the engine and replaced the seal.

We departed two days later for the west coast departure point, McClellan AFB in Sacramento CA. This part of the trip proceeded without a problem. The C-130E model had two large external fuel tanks to increase the range. For various reasons, the external fuel tanks were removed and were placed inside the cargo compartment. The fuel carried inside wings was enough for the longest part of the flight, from Sacramento to Hawaii.

The next morning we departed for Hawaii. We had just been transferred from the FAA Center to the over water controlling agency when we received a low oil light. Visually checking the engines, number three engine was smoking. The turbine seal had failed again. We shutdown the engine and contact the FAA Center and requested a return to McClellan AFB. Arriving back at McClellan AFB, the support person wanted to know why we didn't continue on to Hawaii on three engines. We noted, that without the fuel in the external fuel tanks, there was an hour in the middle of the flight that we could not make land if we lost an engine. Because the same engine was involved, I demanded a new engine. This was delivered in a couple of days. The rest of the return mission went without a problem.

Photos in MISC section.

When one of the C-130 special operation units was unable to support all of their requirements, the tactical C-130 units picked up some of the easier missions.

The tactical C-130 operation was operating out of Cam Rham Bay. The mission was to deliver phy ops leaflets to area over the Ho Chi Min trail in Laos. The cargo compartment was complete filled with boxes or leaflets, even on the ramp. This made the aircraft very tail heavy. Backing out of the revetment was very interesting. Once you got the aircraft moving backward you couldn't touch the brakes. If you touched the aircraft brakes, the tail would settle backward on the ramp.

The mission would depart Cam Rham Bay gaining some altitude before heading west toward Laos. The requirement for using supplemental oxygen began above 10,000 feet. If you flew about 10,000 feet, auxiliary oxygen was required. Some of the crews that flew these missions flew as high as they could go, about 18,000 feet. While the oxygen requirement for the flight deck crew was the same, we would be sitting and it didn't impact us. The loadmasters and other support people in the cargo compartment had to drag long oxygen hose around while pushing boxes.

After discussion with the loadmaster, we elected to fly at 9,500 feet in order to delete the oxygen requirement. The effects required by the loadmasters were still enough that they had to go to the auxiliary oxygen system every few minutes. Since I believed that we were a crew, I left the co-pilot to fly the aircraft while I assisted in the rear of the aircraft for a few minutes.

The boxes, as I remember, were about five feet high and weighed about 70 pounds or so. There was a cord that ran down the middle of the box to the bottom. This cord was then connected to the static line in the aircraft. When the box was pushed out of the aircraft, the cord down the inside would turn the box inside out, dumping the leaflets.

The Army had a Special Forces unit in Okinawa. This was one the units that the C-130s flying out of CCK would support. The Special Forces had a requirement to get so many parachute jumps in a specific period in order to continue to get they jump pay. They would request a C-130 from CCK to come up and provide a platform for them to jump.

I was scheduled to support the Special Forces and the Air Force CCT. The Air Force CCT needed to make some HALO jumps. This would require the C-130 to fly at 10,000 feet. The CCT would jump from that altitude and free fall to some defined altitude where they would open their parachutes. The drop zone was on Ie Jima, an island just north of Okinawa. This is the island that Erine Pile dead on in World War II.

On the next day, we were supporting the Special Forces. Their drop zone was a n old Japanese airfield (Yomitan Aux Airfield) located about 2 miles north of Kadena AB. We loaded up the cargo compartment with special forces troops. Because of the extra equipment, the aircraft held less people than when carrying passengers. The first pass went without a problem. On the second pass, we got a propeller low level oil light. This required the engine to be shutdown, which was accomplished. Rather then return to Kadena, we elected to continue the drops on three engines. The Air Force CCT on the ground asked if we had one standing at attention, which we said was correct. After the last troop departed the aircraft, we recovered at Kadena without a problem.

We returned to our loading point, shutdown the other engine on the side with the engine with the low oil. We took the ladder from the aircraft, and refilled the propeller reservoir. The crew chief (maintenance type) completed this task. We checked for leaks, finding nothing, we restarted the engines, loaded more Special Forces and finished the mission.

There are other stories that occurred during this mission but I'll leave these untold.

Fighter aircraft are designed to withstand much higher "G" forces than the C-130. The C-130, as I remember, had positive "G" loading or 3.0, or 3 times the pull of gravity. We were flying a cargo support mission in Thailand out of U Tapao AFB. Our last stop was at Ubon in NE Thailand. While passing through base operations, an F-4 pilot approached us about a ride to U Tapao. The mission went as planned. We decided to do a low pass down the runway and pull up into a downwind. The pass down the runway was at about 200 knots. The pull up was at 2.5 G's. The fighter pilot was standing behind me and the pull put him on the floor. He thought we had pulled a lot more G's but he was use to sitting and pulling G's.

I always felt that everybody was part of the crew. While each member of the crew had a specific task to complete, I felt that other members of the crew should understand these tasks. In that light, I permitted other members of the crew to experience a landing from the copilots seat (I was an instructor pilot at the time). I also required the copilot follow the flight engineer around during the preflight. During most cargo missions in VN, the crew would work together to offload and reload the aircraft. I worked with the navigator on sexton shots.

I remember on one flight the squadron commander was flying with us. We were loading five pallets of class "A" explosives at a base in Thailand. I assisted loading the pallets as per usual. The squadron commander approached me and said that he felt the aircraft was loaded incorrectly. I said that it was OK. So the squadron commander went through the entire loading using the load and balance slide rule. Guess what, the load was OK. I never questioned the loadmaster.

We were moving the US Marines from Vietnam to Thailand. The mission was a basic cargo mission between Da Nang and a base in Thailand. The crew worked together during the loading/unloading. After takeoff, part of the crew would sleep. We logged a lot of actual airtime that night. I think we got nearly three complete trips.

As the war ended, the 314th was tasked to move an Air Force air unit from DaNang to northern Japan, in the winter to boot. Because of the Jet Steam, the trips northbound were fast. A crew would launch from CCK and fly to DaNang. There they would load up the aircraft and return to CCK. At CCK the passengers would be feed and the crew change made. The new crew would then fly north. My crew was tasked to fly this northern leg. The inbound aircraft reported maintenance status and if OK, the new crew was called.

After refueling and reloading, we took off. Because of the 150knot jet stream tail wind, the northbound leg went very fast. As I remember, we had a ground speed at one time of over 450 knots. The landing was no problem but Northern Japan receives a lot of snow and is cold. So these troops from Vietnam would step off the C-130, coming from Vietnam and 75-85 degree temperatures into near zero temperatures, strong winds and three feet of snow. There were members of the local unit available at the aircraft door handing out cold weather gear to the arriving troops.

The inbound crew would stay overnight and the aircraft would return with another crew taking the aircraft back to CCK. The next day, we were called for the return mission. We were now flying directly against the jet stream. The quick northbound trip turning into a slooooow return trip. Overall, flying through the jet stream was fairly smooth. However, coming out of the side of the stream was very rough. I would say that this was the worst I have every been bang around while flying.

After you upgrade from copilot to aircraft commander, you normally get a fairly easy mission. The squadron tends to place an experience crew with you to see how you do. My first mission after upgrade was a cargo mission to Yokato Japan. It was an easy mission except for the poor weather in Japan. This would require an instrument approach. About an hour out, we had some warning indicator which required an engine shutdown. So my first landing as an aircraft commander was a GCA in actual weather with an engine out.

When I first started flying in Vietnam, we normally flew in fatigues. These worked great as you could take the top off when on the ground and it was hot. The normal Air Force Flight suit didn't really fit me so the fatigues worked great. The Air Force then came out with the nomex flight suits and after this we were required to wear these along with gloves. I was able to trade the army for couple of set of army two piece nomex flight suits. I wore this until the Wing Commander directed only Air Force flight suits could be worn.